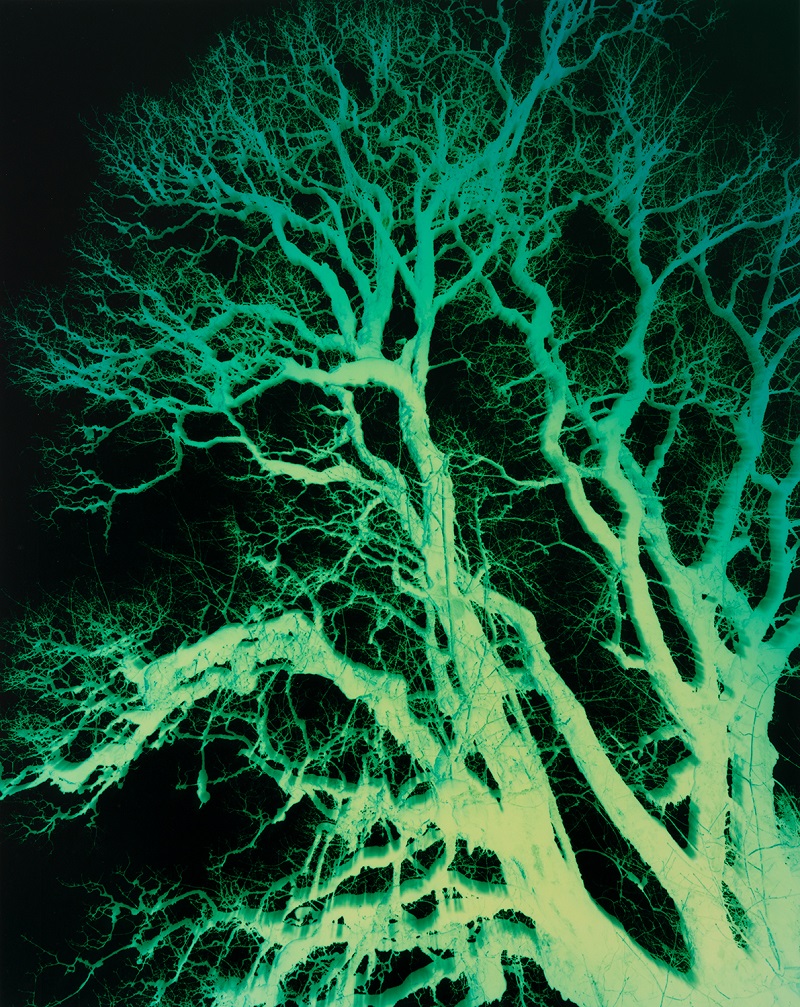

The Photopoetry approach of Peter Hauser

Peter Hauser is a Swiss photographer and artist based in Zurich, known for his work with analog and camera-less photographic techniques. He operates his own darkroom, where he works on handmade printing and experimenting with alternative photographic processes. Peter was nominated twice for the Swiss Federal Design Awards (2012 and 2016). His first monograph “Hello, I am not from here” was awarded The Most Beautiful Swiss Books in 2016.

Numéro Switzerland: Peter, if you had to distill your visual universe into three words that aren’t “photography,” what would they be?

Peter Hauser: Inquisitiveness, play, contemplation.

NS: You studied at the Lucerne Art School, The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague, and Zurich University of the Arts: three schools, three distinct cultural sensibilities. How did each of these environments shape your visual philosophy and the artist you’ve become?

PH: The good thing about institutions is that you are noticed. Discourses arise with people who either know more than you do or with people who are just as lost as you are. These are not bad conditions, really. Luckily, I was never in a master-apprentice relationship. I think that saved me from having the signature style of other photographers imposed on me. After all, what I probably learned most from art schools is that, in the end, you are on your own.

NS: Your journey from student to professional artist feels like an evolution of vision. Was there a particular moment when you recognized your own visual language emerging, when intuition and technique finally converged?

PH: I like the term ‘evolution of vision’. You could also call it ‘evolution of life’. I keep coming back to points where something new happens, where new visions and ideas arise, which are then reflected in my photography. These are key moments that sometimes come over me quite unexpectedly. It can happen anywhere, anytime. It has nothing to do with chance. I believe more in constant, disjointed reflection on things and circumstances, on life in general. And sometimes such thoughts connect in my brain and an idea is born. And then there is this huge pool of technical possibilities that I have accumulated over years of experimentation in the darkroom. And suddenly things converge.

NS: You’ve moved fluidly between still life, architecture, portraiture, and landscape. What is the connective tissue between these genres in your work, what aesthetic or emotional thread unites them under your gaze?

PH: I mentioned inquisitiveness before. I have always found it hard to limit myself to one thing or focus on just one genre. That’s just not me. The world is too colourful and diverse for that. In the short term, this might mislead viewers. But that’s none of my concern, really. I see my work as part of something bigger, as an unfinished whole. It is an eternal search, an eternal trial. So perhaps it doesn’t matter which genres are covered and which aren’t. Behind every picture, there’s me as a human being, as a searching, curious cosmopolitan.

NS: The notion of “the world behind appearances” seems to pulse through your practice. Do you believe photography can truly render the invisible visible? And how would you define that invisible layer you are seeking to reveal?

PH: Photography is definitely a magical medium; it always has been. The first attempts to capture light in the early 19th century were reminiscent of magic. Or think of spirit photography at the turn of the last century. In reality, it was just double exposures, light was captured twice on the same light-sensitive surface. Something invisible to our eyes became visible, but people believed that spirits were being photographed. Photography therefore also has a lot to do with illusion and storytelling. The mystification of the world by humans is an old story. With old fairy tales, we don’t know whether these stories really happened or whether they are invented. And painting works the same way. What I mean by this is that photography has the power to invent and tell magic stories. So if my pictures tell miraculous stories that make people think about what hovers above and around us or make them look at things differently, I’m satisfied.

NS: The title In Search of the Miraculous evokes both a spiritual and a visual pilgrimage. What does “the miraculous” signify to you within the language of photography?

PH: The invisible, the miraculous happens outside my pictures, on a different level. It is the level of contemplation, of reflection. I invite viewers to enter this level.

NS: Your recent work often transfigures familiar landscapes into something ethereal, almost hallucinatory. How do you approach the selection of your locations or subjects — such as in your recent La Vue-des-Alpes publication exploring I.S.O.T.M., created with handmade analogue C-prints?

PH: For the exhibition at La Vue-des-Alpes, which took place in a specific landscape in the Swiss Jura, I wanted to work specifically with this habitat. Thus, I had studied and captured fragments of the territory where the outdoor exhibition was taking place. The idea behind this was that visitors could compare my transformed images of landscapes with the actual landscape in which they were taken. With this effect, I hoped to encourage reflection on our viewing habits and how we perceive landscapes. But it can also happen that I find myself in a place without any particular destination in mind and simply let myself drift, observing plants and feeling overwhelmed.

NS: In what sense does I.S.O.T.M. mirror your personal search for meaning or communion with nature?

PH: I am currently reading a lot about the term “nature”. What does nature actually mean, and does such a thing as nature even exist anymore? Has what we call nature been transformed into culture by humans over the centuries? I came across the term ‘anthropogenic landscape’. It means that landscapes have long been areas of land that have been worked and altered by humans. Can we still talk about nature in this context? Or think about water, air and soil: they have all been influenced and contaminated by humans. It seems as though we must bid farewell to the idea of ‘nature’ as a place of the original, the natural, the untouched. At the same time, I believe that there is something on this planet that cannot be corrupted by humans. I am thinking here of the supernatural, the miraculous, energies and spheres. Perhaps we will have to seek nature in these realms in the future?

NS: Despite today’s digital immediacy, you remain deeply attached to analogue processes. What compels you to sustain this tactile, hands-on relationship with the photographic medium?

PH: For me, photography is something very physical. Taking pictures with a camera, moving around, looking for the right frame, holding the device, etc., it’s all very intense. Thus, it makes little sense to me to discard this physicality once the pictures have been taken. This process of physicality continues when I take the film material into my hands, when I stand in a dark room and expose the paper, and my pictures finally become a physical entity.

NS: And finally — what has been your own miraculous moment — that intimate reminder of why you continue to create?

PH: For me, most magical moments happen when developing colour paper in the darkroom. It’s incredible to see so many different colours slumbering in this light-sensitive paper. You just have to search for them, as if you were mining for gold. That’s miraculous!

NS: There’s an almost monastic patience in the way you build images. What does waiting mean to you, both as an artist and as a human being?

PH: I have learned that if you keep doing something over and over again and remain patient, you will master it.