Pavel Kir, Unveiling the Invisible

Over the years, Kir has navigated various media, wielding the line with surgical precision and embracing color as an elemental force. His work thrives on contradictions: restraint and excess, precision and chance, beauty and its deliberate subversion. Yet, one thing remains constant in all his explorations—his pursuit of something beyond himself. In this conversation, we discuss the battle between line and color, the moral weight of art, and why, in the end, the most fascinating thing on Earth is still people.

jacket, shirt, and trousers CORNELIANI

sneakers HERMÈS

coat PRADA

scarf and trousers HERMÈS

ABSINTHE, SERIA III. LA MUJER

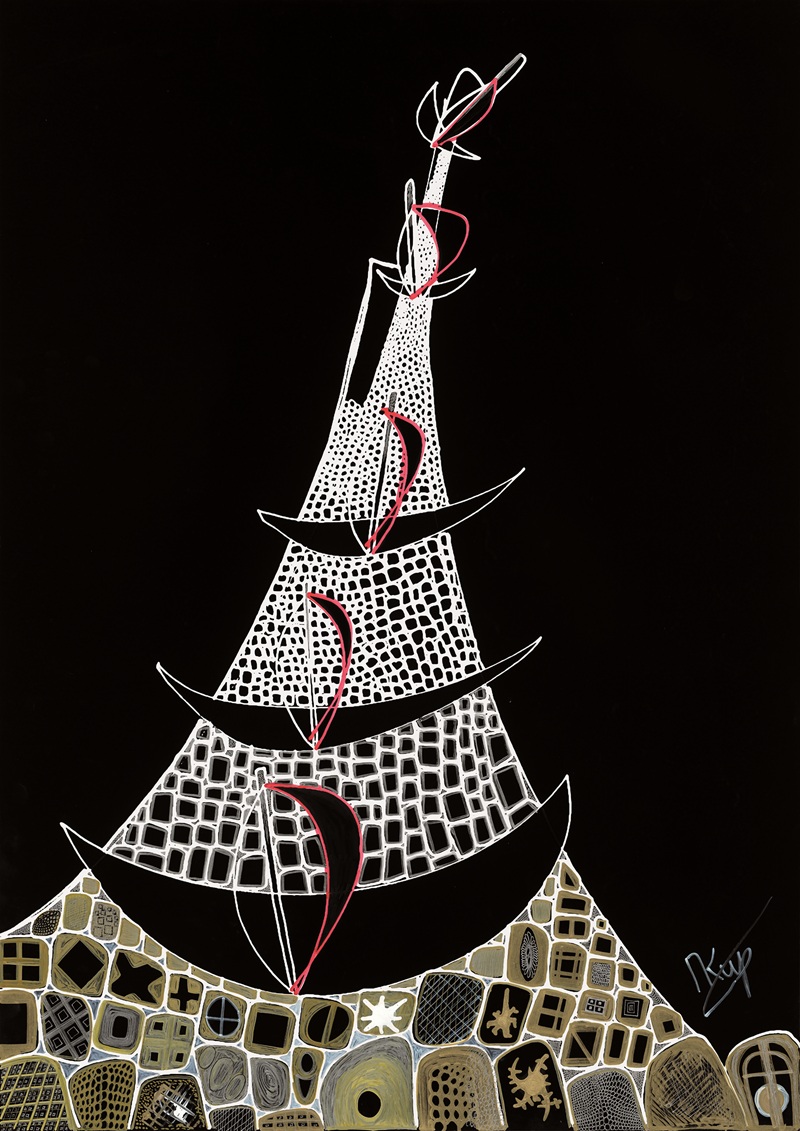

THE CLOWN, SERIA I. THE DARK ONES

Q: You once said that art is not created but revealed. Could you elaborate on this idea?

A: I value the works that meet two criteria. First, I can return to them again and again. I never tire of looking at them, even if they’ve been hanging on the wall for years. There’s something in them I still haven’t deciphered. Second: I don’t believe I made them. It feels like I uncovered something that lies beyond my soul. It comes from outside. Call it what you will, but I know for sure that God was near when it was created.

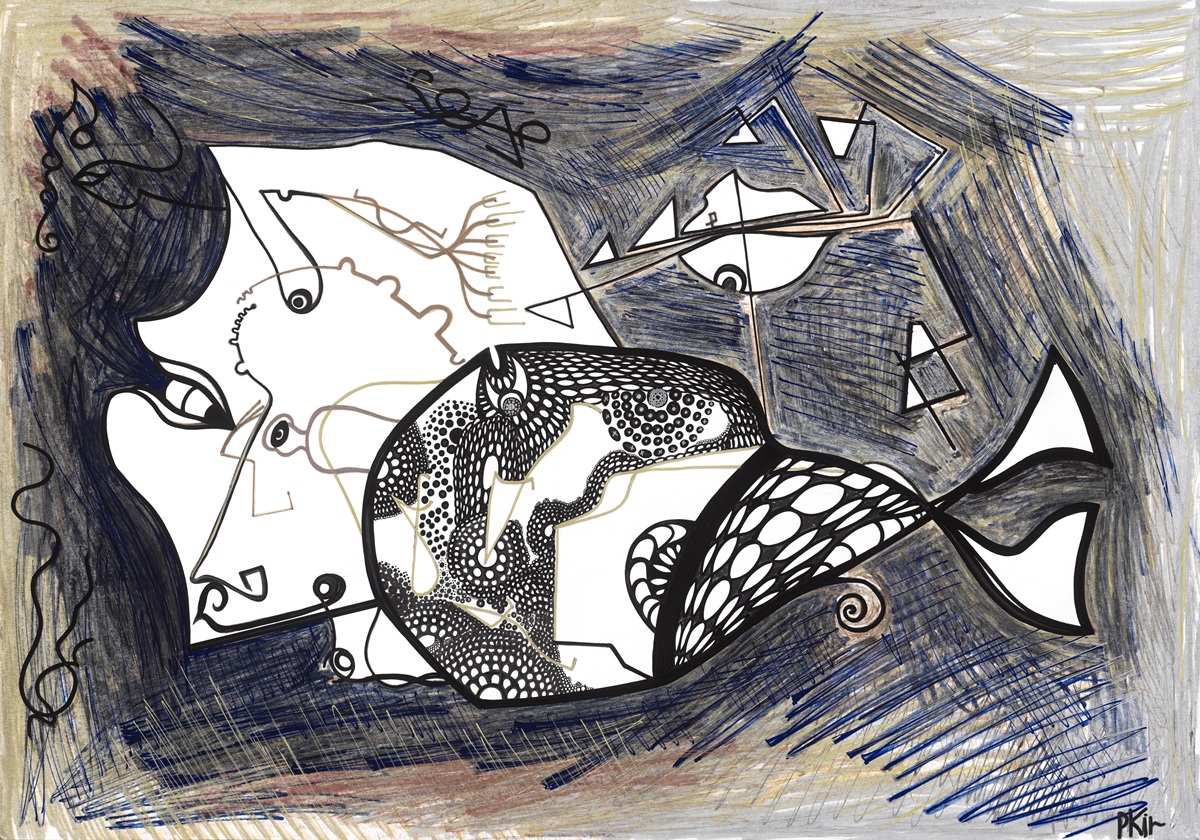

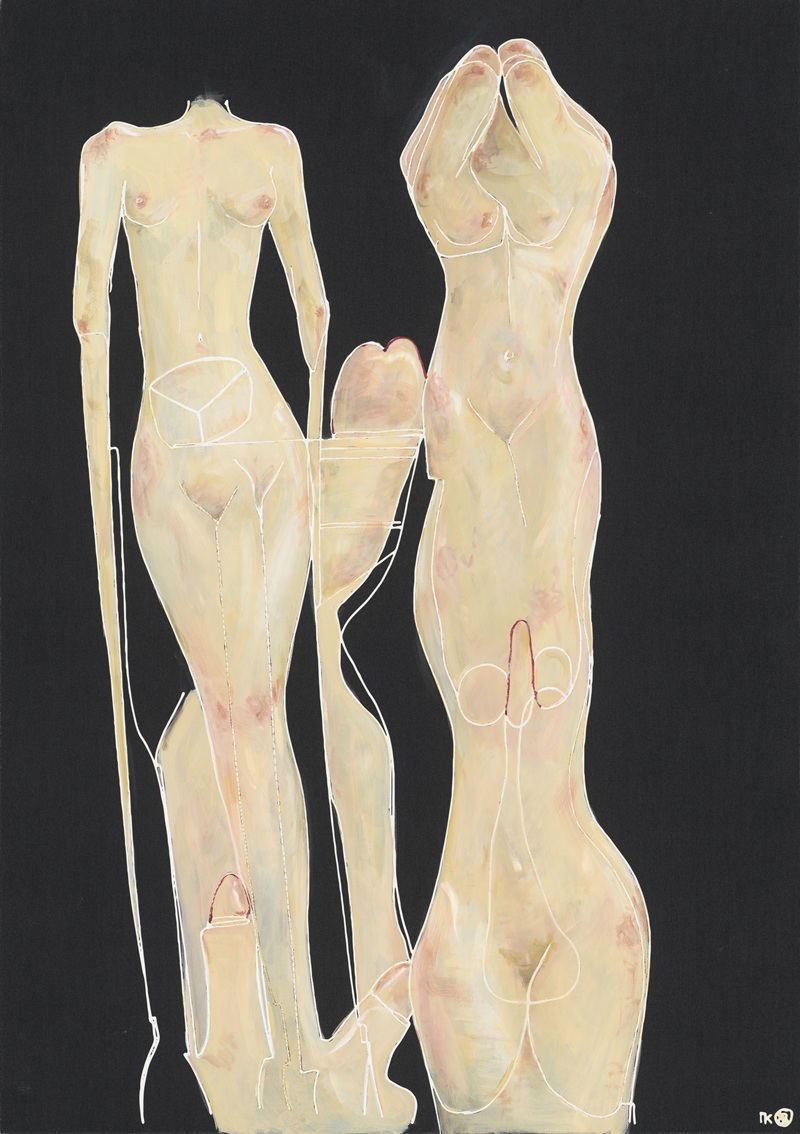

FISH: WOMAN AND MEN AS VICTIMS OF SEXUAL DIMORPHISM, SERIA III. LA MUJER

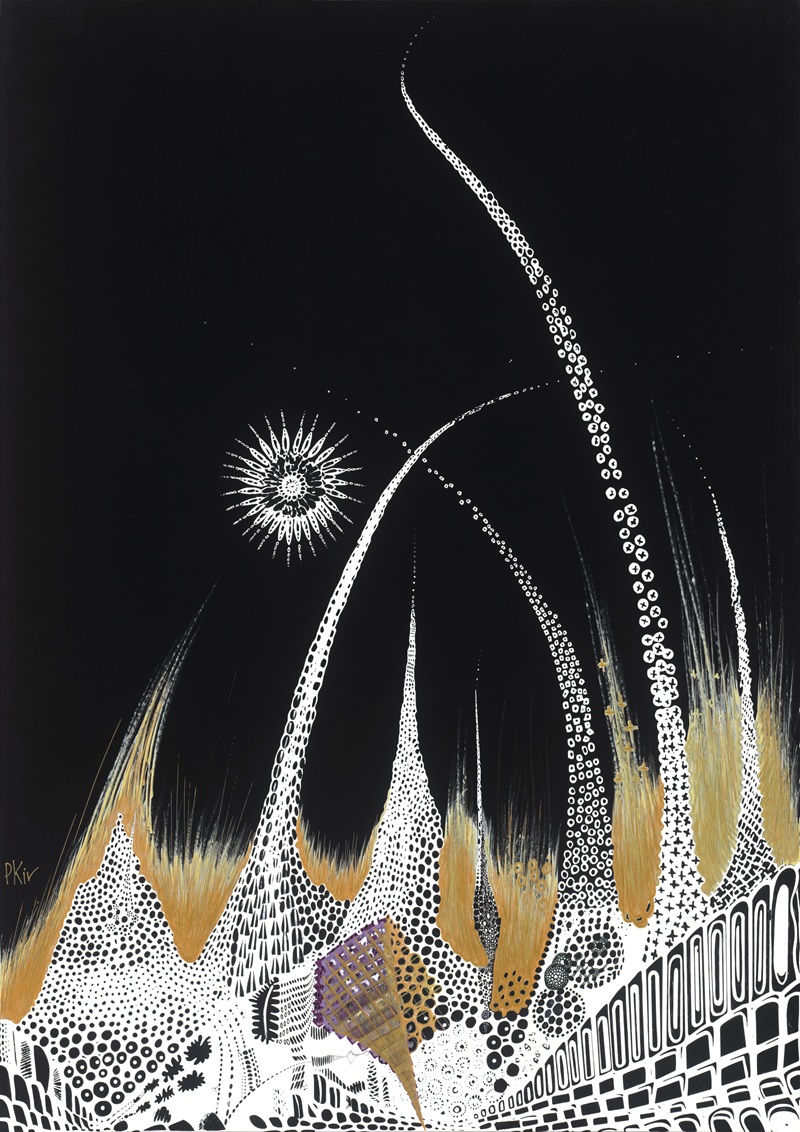

POLAR KIDS, SERIA III. LA MUJER

Q: You’ve worked in various media—from graphics to oil painting. What brought you back to the line?

A: The line is my scalpel. It cuts through the reality I see, makes it clearer, and strips away the shapeless and inexpressive. I love color too, but it has a certain excessiveness I sometimes want to escape. Just look at how the eye rests when you shift from color images to black-and-white. There, it’s the edge—the line—that defines everything. For me, the line is not necessarily stronger than color, but it’s the first to enter the work and the last to complete it. Look at the “funny” parallelepipeds in Bacon’s Study for a Portrait of Pope Innocent X—they’re not funny at all. There’s megavolt energy in those lines. But the war between line and color never stops inside me. On color’s side are black, white, red, and metallic. Why exactly those—I still don’t know.

Q: You’ve said the art world is divided between those who work with line and those who work with color. Why are these approaches so different, and what is it about the line that resonates more deeply with you?

A: It’s astonishing—how heavy Van Gogh’s drawings are, and how insignificant color is in Dürer. You don’t want to cheapen Beardsley with color, and even those who parody the Mona Lisa never turn her monochrome—they don’t reduce her to the line. Or take this: why does Malevich’s White Square still remain Black Square in our minds? I don’t see color there—I feel energy from geometry. And on the other hand: with Rothko, it’s only color—and only color gives off the energy. Of course, there have been geniuses in history who could fuse both, but that’s rare. Why some work better with color and others with line—no one can explain. I don’t choose—I just pick up the pen. It’s my scalpel. It carves out the image. Then color comes—to heal the wound.

BIRDIE, SERIA I. THE DARK ONES

DUBAI, SERIA IV. THE PLACES

Q: In your opinion, what role does beauty play in contemporary art? Has it been abandoned in favor of concept and critique?

A: Contemporary art, in its simplified form, still sets itself in opposition to classical art—to anything beautiful. To depict beauty beautifully is to open yourself up to banal criticism—“millions before you did it just as well.” But beauty, subtly, still remains the ruling force. Even Bacon’s copulating flesh is, in its own way, beautiful. There’s the struggle of color, the magic of composition, the clash of the incompatible. What’s not beautiful—that’s what 80% of New York galleries sell. That’s what’s bought by people collecting someone else’s sunsets and someone else’s lovers. Try, for once, drawing—or at least photographing—your own.

Q: Do you think the perception of beauty is shaped more by culture, experience, or by an innate instinct?

A: I don’t think there’s such a thing as an innate sense of beauty. But the fact that both cultured and uncultured men are drawn to the same women—there’s definitely something innate there. Of course, culture, age, gender, and experience all play a part. But more importantly: do you look out the window at the sunset as the plane rises above the clouds? Or, like most people—don’t? Understanding beauty is a form of personal wealth. Yes, people in Tokyo benefit from the tradition of watching the cherry blossoms, and Romans—from ruins, but I fear not everyone in Cairo even looks up at the pyramids. Many simply don’t have the strength. Beauty is the boundary between the living and the dead.

Q: You’ve said you don’t use an eraser—not out of confidence, but a desire for honesty. How has that philosophy shaped you?

A: Leonardo died five hundred years ago—it’s time to stop being embarrassed that as an artist you can’t draw a smile as well as he could. Besides, a photograph will always be more precise anyway. I know that many of my early drawings are full of inaccuracies. One angel, for example, has a terrible leg. Erase it? Redraw it? No. I want Great Chance and Great Time to stay with me. Maybe they’ll bless me again.

Q: Do you believe art carries moral responsibility? Should it comfort, challenge, or simply exist?

A: It’s hard to say, but I can tell you what resonates with me. First: I love and dislike in an artist the same things I do in any person. When I see the businessman kill the artist in Hirst or Dalí—it repels me. When an artist sings the same tune their entire life, like Chagall—I just walk past. Second: it’s always the artist’s choice. In my The Dark Ones series—it’s neither a celebration nor defense of evil. It’s an acknowledgment: darkness exists in all of us.

Q: You’ve said people are the most interesting thing on Earth. How has your interest in psychology and “human-studying” shaped your art?

A: My art and my interest in people are one and the same. I’ve studied people all my life. And I’m not done. At MoMA in New York this March, I was watching not just the paintings but the people looking at them. To me, they were just as much art as what was on the walls. I felt the same way at the Guggenheim the day before. I want to explore this further in a photo project this autumn. A person is not one species (I mean, humans themselves consist of different species! I’ll write or talk more about this later). That’s what I try to convey in my work—with varying success.

Q: Is there a moment in your life that you return to—consciously or not —in your work?

A: That would be the adolescent discovery of myself as an artist and poet. The first unrequited love. That longing from nowhere. That sequence of numbers—8, 22, 88. And the realization that I never got to speak with my father, a bishop who warmed the souls of others—but never reached mine. He died when I was two. I still dream about him. Those unspoken conversations—they stay with me.

MAYBE SHE REALLY LOVES F…, SERIA III. LA MUJER

FUCKING EXIT

NK, SERIA IV THE PLACES

CHILDHOOD, SERIA III. LA MUJER

Q: Has contemporary art become too literal? Too explanatory?

A: Yes. But it’s inevitable. Luckily, it’s not as tragic as cutting off your ear or jumping out the window. You don’t have to do that anymore. Sometimes, you can just explain yourself. Although when Pavlensky nails his scrotum to Red Square—that still works. The artist and his gesture have long been one and the same. How he speaks—or remains silent—is part of his art. And I agree with Bacon: the artist doesn’t know what he has depicted. Recently, a well-known watercolorist in his hometown, who paints dishes, told me his art is more layered than mine. I agree. I haven’t painted dishes yet. You can drink from them. I wouldn’t.

Q: Looking back, is there one work that feels most personal to you?

A: A chance line, drawn with a scalpel-pen. Reflecting time. The feeling that one day—it stopped. Along with time itself. Pavel Kir has become a painter, draftsman, and thinker of international standing, whose work engages with the philosophical on the one hand, and visceral engagement on the other really deep. The classical tradition and modernist deconstruction inspire him to create works that bring the viewer to a place where form and meaning change upon closer inspection. His The Dark Ones series, most often misinterpreted as a study in darkness itself, is simply an acknowledgment of the shadows that live within us all. Kir’s artistic philosophy refuses to simplify—his pieces are in no way statements but inquiries, fragments of a larger and unfinished conversation between artist and observer.

FISHY, SERIA III. LA MUJER

coat BALENCIAGA

turtleneck MASSIMO DUTTI

trousers HERMÈS

PAVEL KIR

author ANASTASIA YOVANOVSKA

artwork and talent PAVEL KIR

photographer DANILO PAVLOVIC

stylist MARKO MRKAJA