Time, Silence, and the Space Between – A Conversation with Ugo Rondinone

In Ugo Rondinone’s universe, emotion lives in stone, colour has its logic, and time becomes slow and radiant. Born in 1964 in the lakeside Swiss town of Brunnen, with roots in the sun-bleached cave city of Matera that run deep in his family, Rondinone spent his childhood between two elemental landscapes: one defined by water and snow, the other by earth and silence.

That duality—light and dark, presence and absence—has shaped his work.

From mediums as diverse as neon, bronze, pigment, and sound, Rondinone constructs spaces that feel intimate, vast, personal, and mythic. To step into a Rondinone installation is to enter a meditative trance. His clowns sit in silence, bearing the weight of the everyday. His rainbows hang in the sky like fleeting prayers. His monumental boulders, painted in eye-searing hues, rise like ancient sentinels in the Nevada desert. An artist returns repeatedly to cycles—of the sun and moon, waking and dreaming, solitude and communion—as if to say: this is the proper rhythm of being alive. For Rondinone, art is not an explanation; it is presence, attention, and the primal act of paying attention to what has always been present.

ANASTASIA YOVANOVSKA What is the first piece of art you remember creating, and do you think it still influences your work today?

UGO RONDINONE In 1988, while studying in Vienna, I created a group of flower sculptures using white plaster. As a secret ingredient, I mixed plaster dust with water and added a bottle of poppers. This group of sculptures became a guiding principle and a strategy I still employ today: making something simple like a flower and adding hidden information to enhance its mental potential. The hidden secret doesn’t need to be revealed to the viewer—only I need to know it’s there.

The medium is a prosthesis, a tool, a coexistence. It paves the way for diversification and thus thwarts the construction of uniformity. Each medium has its force and historical memory.

AY Your work spans various mediums—painting, sculpture, neon, and installation. How do you determine which form an idea should take?

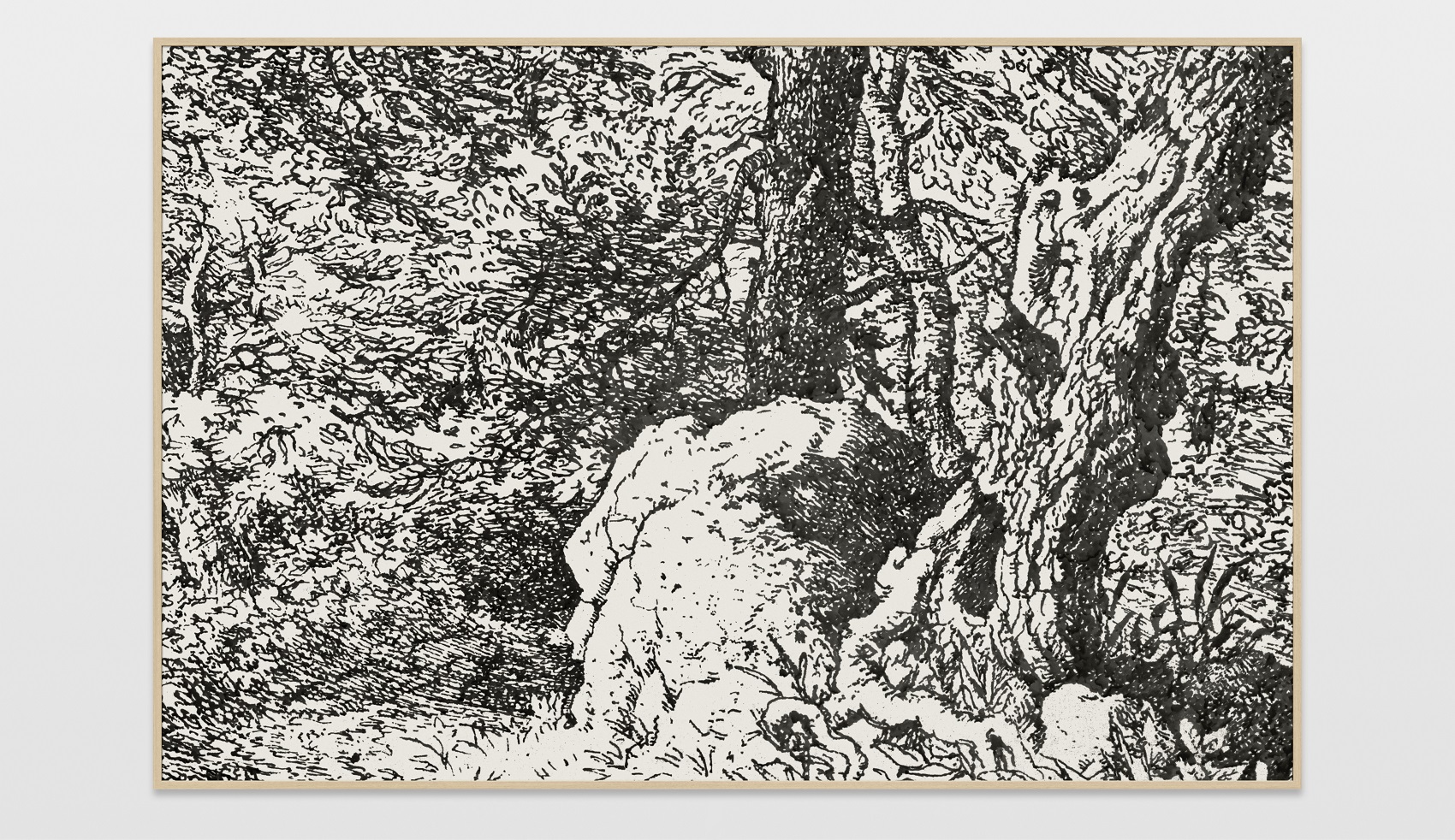

UR The medium is a prosthesis, a tool, a coexistence. It paves the way for diversification and thus thwarts the construction of uniformity. Each medium has its force and historical memory. Each is equally important to me. Depending on what is to be achieved, I choose the best one for the task. In general, my work is embedded in the observation of nature and its relation to the human condition—connecting us with our sources in the natural world: its beauty, terrors, and mysteries. Using different mediums like painting or sculpture involves an investigation of their mutual potential —as both physical mediums and sites of rich cultural disclosure in art.

AY Your pieces often emphasize cycles—day and night, time passing, and repetition. Do you perceive art as a means to reconcile with the concept of impermanence?

UR Through art, I celebrate life: its seasons and rhythms, plants and stones with which we share the planet and our lives. Like a diarist, I record the living universe: this season, this day, this hour, this sound in the grass, this crashing wave, this sunset, this end of the day, this silence. I see the world as a mysterious place where appearances are deceptive, and ultimate reality is rarely perceived. A world where everyone creates their own time and space. It’s a paradox: on one hand, we experience time and space as reliable and predictable, while on the other hand, they present us with a deceptive form of reality. The inner nature of time and space is gloomy, labyrinthine, and perilous. My work is spartan, simple, and rhythmic—sometimes bordering on singsong. I aim to avoid the appearance of cleverness. The work is observational and direct. It is what it is—not a labyrinth, nor does it require a degree or footnotes. It’s like looking at a tree each morning and noticing something new. The work is meditative. My most common subject, nature, may cast me into a genre that is seen as passé or unfashionable. But my nature is the nature of movement through the world—observational and in the moment.

AY Seven Magic Mountains is a stunning blend of natural stone and vibrant colours. How did you develop that concept, and what challenges arose from working at such a large scale?

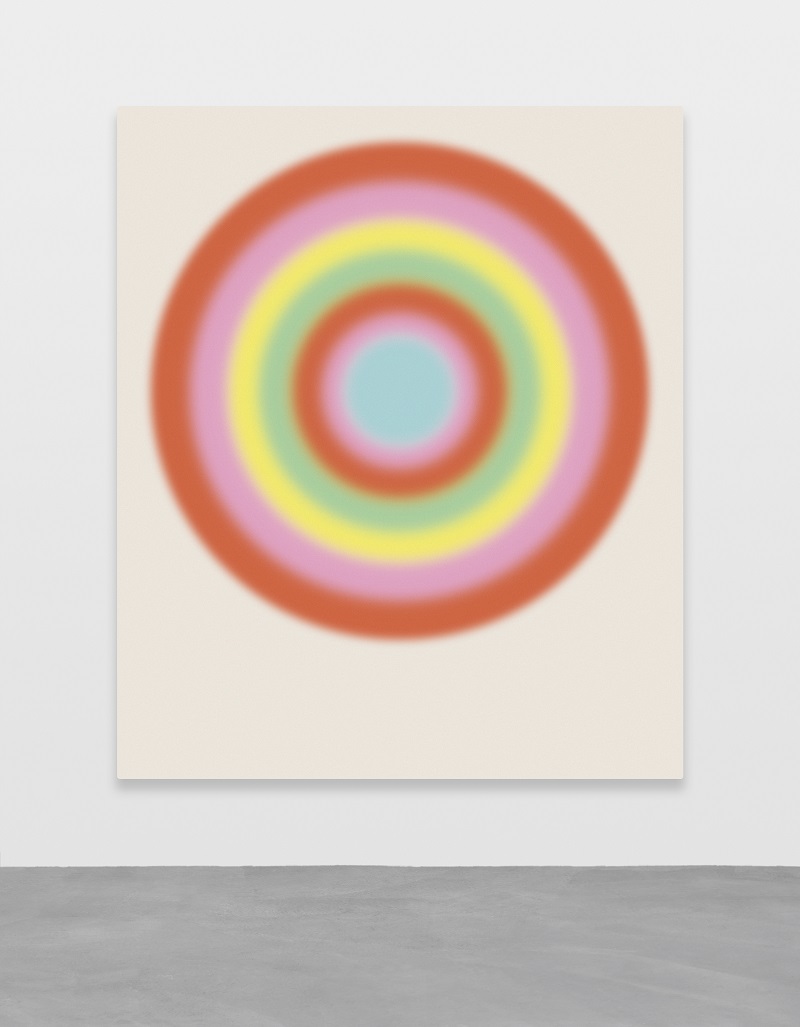

UR The Seven Magic Mountains project consists of seven towering stone sculptures made from fluorescent-painted Jericho boulders stacked to form mountains. Each sculpture is positioned at a short distance from the others, together creating a labyrinth of canyon-like passageways. My website is divided into two sections: Night and Day. Night showcases all works that are either black and white or utilise the natural colours of materials such as bronze, aluminium, or stone. Day presents works that employ the colour wheel and rainbow spectrum. This interaction allows both black-and-white and coloured works to complement each other. This interdependence is best illustrated by two outdoor projects, Human Nature at Rockefeller Center in 2013 and Seven Magic Mountains in the Nevada desert in 2016. Both projects utilised stone as the primary material. At Rockefeller Centre, an epicentre of urbanism, I kept the stone in its raw state. In the desert, I painted it in day-glow colours. This is a play of contrasts between natural and artificial environments. With raw stone figures, I brought the classical elements of Land Art into the vibrant city. With colourful stone mountains, I employed strategies from the Pop Art movement and integrated them into nature.at a tree each morning and noticing something new. The work is meditative. My most common subject, nature, may cast me into a genre that is seen as passé or unfashionable. But my nature is the nature of movement through the world—observational and in the moment.

AY Can you walk us through a typical day in your studio? Do you follow a specific routine?

UR In 2014, I wondered if I could create a work that represented my daily life and routine. That led to Vocabulary of Solitude—a work showing 45 clown sculptures, each sitting, sleeping, or contemplating. Each clown represents an activity over a 24-hour cycle. The 45 activities are: be. breathe. sleep. dream. wake. rise. sit. hear. look. think. stand. walk. pee. shower. dress. drink. fart. shit. read. laugh. cook. smell. taste. eat. clean. write. daydream. remember. cry. nap. touch. Feel. moan. enjoy. float. love. hope. wish. sing. dance. fall. curse. yawn. undress. lie…

AY Your clown sculptures perfectly capture a sense of melancholy. What led you to explore the figure of the clown?

UR A clown is a recognisable, non-binary character with outlandish costumes, exaggerated makeup, colourful wigs and clothing, designed to entertain. Doesn’t that sound like a drag queen? In the early ’90s, during the AIDS crisis, I began using the clown as an alter ego—a gay artist, an outcast, someone people feared. And isn’t there a direct link between artist and entertainer? But what if the clown just sits and contemplates? What if the artist has nothing to say and nothing to defend? With this passive figure, I wanted to escape the pressure of performance, to give myself the freedom to create by my own rules. I turned the clown, the entertainer, into someone who doesn’t entertain but simply reflects.

AY Can you walk us through a typical day in your studio? Do you follow a specific routine?

UR In 2014, I wondered if I could create a work that represented my daily life and routine. That led to Vocabulary of Solitude—a work showing 45 clown sculptures, each sitting, sleeping, or contemplating. Each clown represents an activity over a 24-hour cycle. The 45 activities are: be. breathe. sleep. dream. wake. rise. sit. hear. look. think. stand. walk. pee. shower. dress. drink. fart. shit. read. laugh. cook. smell. taste. eat. clean. write. daydream. remember. cry. nap. touch. Feel. moan. enjoy. float. love. hope. wish. sing. dance. fall. curse. yawn. undress. lie…

AY Your clown sculptures perfectly capture a sense of melancholy. What led you to explore the figure of the clown?

UR A clown is a recognisable, non-binary character with outlandish costumes, exaggerated makeup, colourful wigs and clothing, designed to entertain. Doesn’t that sound like a drag queen? In the early ’90s, during the AIDS crisis, I began using the clown as an alter ego—a gay artist, an outcast, someone people feared. And isn’t there a direct link between artist and entertainer? But what if the clown just sits and contemplates? What if the artist has nothing to say and nothing to defend? With this passive figure, I wanted to escape the pressure of performance, to give myself the freedom to create by my own rules. I turned the clown, the entertainer, into someone who doesn’t entertain but simply reflects.

AY Who or what were your biggest influences when you first began creating art? Have those influences changed?

UR I’ve always been inspired by poetry. There’s an inherent slowness in poetry—and in art. It allows for the experience of words and images unfolding. Slowness, unlike speed, doesn’t make demands. It doesn’t pull me out of time, but allows me to be. Poetry and art stretch time—nothing is over or done with. Everything can recur or be revived. The past, present, and future loop together like dream symbols and voices. A poem or artwork is a multivocal chorus without linear logic.

AY You’ve lived and worked in various locations—from Switzerland to New York. How has geography influenced your artistic vision?

UR I started as an assistant to Hermann Nitsch at 21. After six months, I left and studied under Bruno Gironcoli at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna. I stayed in Vienna for 10 years, spent five years in Berlin, and then moved to New York in 1997. Mobility keeps me focused and sharpens my mind. My family background and the environment I grew up in provided me with values and visual reference points. I was born in Brunnen, on Lake Lucerne. My parents emigrated from Matera, thought to be the third-oldest continually inhabited city after Aleppo and Jericho. My father, a mason, came to Switzerland in 1959, and my mother, a seamstress, joined him in 1963. I was born on November 30, 1964. Until I was 7, I divided my time between the colourless stone city of Matera and the fairy-tale setting of Brunnen. That contrast defined my value and image system. You can never escape your roots—they’re where everything begins and from where I continue to draw.

AY Many of your pieces feel personal yet universal. How much of yourself do you reveal in your work?

UR I don’t respond to political events. I can acknowledge mourning, but I see myself as an artist of light. I want to guide viewers toward the sun, toward light that shines on everyone. My childlike works welcome the viewer. I don’t want to build walls; I want to open windows. My first public sculpture was «Cry Me a River» in 1996, during the AIDS crisis. I wanted visibility as a gay man. The rainbow is a bridge between people, places, and ideas. It’s a metaphor for evolving attitudes about the environment and our communities. Nature isn’t outside us—it’s within us. Our civilisations are natural constructs. We must go beyond identity and focus on our shared ground.

AY Is an artwork ever truly finished, or does it evolve based on how people perceive it?

UR IT’s wishful thinking that artwork accumulates power over time and absorbs every moment. I hope it does—but who knows?

Ugo Rondinone’s work reminds us that meaning doesn’t need to be declared—it can simply emerge, slowly, like the light at the end of the day. In a culture saturated with noise and urgency, the artist offers a counterpoint: a return to rhythm, to nature, to the quiet rituals of living. He invites us not to analyse, but to observe. Not to explain, but to feel. And in that gentle shift, we are reminded of something essential—that art, at its best, doesn’t just reflect the world; it softens it, deepens it, and, sometimes, helps us feel a little more at home in our own skin.

author ANASTASIA YOVANOVSKA

images COURTESY OF UGO RONDINONE